“Digital Amalgamations” showcases the importance of the human being behind the technology used to create artworks and how humanity is both affected by, and affects, digital worlds. This exhibition brings together artists Skawennati, Sondi, Shaheer Zazai, Ryker Woodward, and LuYang and sets out to explore how each artist's practice is in conversation with the digital landscapes they portray in relation to markers of their own identity, such as race, gender, age, and situatedness within a post-internet world.

We are all living under a universal notion of existence that Erich Hörl terms the “technological condition”[1]. We have become digital beings that have integrated ourselves into technology, and the technological realm is – known or unbeknownst to us – the framework we operate under. Our existence in countless digital cyberspaces, such as on games, apps, and websites, have blurred the separation between “artificial” reality and physical reality. Thus, we now live in what we might call a "transpacial universe," where we exist and present ourselves as hybrid, plural, and fragmented beings.

The physicality of the artist merges with their digital existences in their artworks, resulting in both a separation, yet also an intertwining, or an amalgamation, between the digital and physical body. The artists in “Digital Amalgamations” showcase this integration and symbiotic relationship between the human and the digital, exploring the multiplicities, (re)imaginings, temporalities, and fluidities of the self.

Home404 by Sondi is a three-channel installation that questions what it means to lack a fixed home while simultaneously occupying multiple spaces. The whole installation adapts to its immediate environment, and allows itself to always expand, adapt, and garner various meanings and interpretations based on their surroundings.

Sondi’s identity as an artist of diaspora is presented in both her depiction of her avatar (that shares Sondi’s physical likeness) and her creation of engulfing fantastical landscapes. Referring to local rituals in Cameroon, her avatar in Home404 is replicated throughout three television screens that make up the installation. Her practice centers around the concept of worldbuilding: creating virtual environments where her memory, ancestry, and imagination enter to contemplate new modes and intricacies of being. Cultural histories and memories of the past intertwine with Sondi’s present, and are all memorialized within digital code.

Highlighting Indigenous people in the future, Skawennati’s artistic practice questions human relationships with technology through her perspective as an urban Kanien’kehá:ka woman and as a cyberpunk avatar. A significant portion of her artistic practice has revolved around the online massive multiplayer community called Second Life, originally released in 2003.

Skawennati’s Dancing with Myself is a life size diptych that pairs a photo of the artist with a “machinimagraph”[2] of her Second Life avatar, xox, taking on the form of fashion photography. She questions: what aspects make an avatar Indigenous? How can she work with, and against software limitations in order to represent herself as a Native woman?

The avatar body, as Treva Michelle Pullen states, “can be used as a fluid and malleable site for the decolonization of Indigenous and other marginalized identities”[3]. However, this avatar identity is not to be alienated from physical land, body, and space [4].

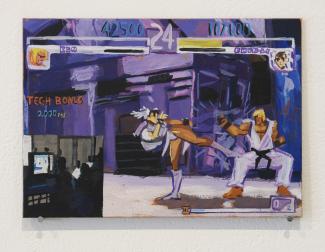

Ryker Woodward’s paintings of video game characters and interfaces always allude to the gaming subject, or the self, who witnesses these gaming landscapes – either through the representation of gaming protagonists, environments, user interface graphics that provide information, or the deliberate presence-absence of the physical controller apparatus. Brendan Keogh, in “A Play of Bodies,” states that the body-at-the-videogame is a particular, augmented version of the player’s body: “[...]identities, abilities, literacies, and perspectives are taken up and put aside [...]” [5]. In this way, the player and video game take on an equal status of hierarchy to one another. Becoming intrinsically intertwined, they work together to present a formation of a body – an avatar.

In Woodward’s paintings, these avatars are characters from nostalgic game releases, rather than direct representations of himself. These avatars, in turn, stand as signals of all of us within the game.

DOKU the Self by LuYang is a video that showcases the multiplicities, disintegrations, and ambiguities of the artist, as well as his ongoing exploration in uncovering the potentialities and limitations of being human – informed by a cosmology of his Buddhist practices, Japanese popular culture, science, and religion. His genderless avatar, called DOKU, is short for the Japanese phrase “Dokusho dokushi”, which means: we are born alone, and we die alone. The phrase references the Infinite Life Sutra Buddhist scripture from the Great Vehicle tradition, a sutra that references a cosmology of realms of rebirth and transmigration. LuYang’s creation and emphasis on his avatar within this work is also evocative of the word’s origins within Hindu incarnation. DOKU is a digital shell for the artist, who acts as a perpetually reincarnated version of himself that houses his soul within the digital realm.

Representation of the digitally intertwined self is seen even beyond the representation of a human body. Shaheer Zazai is a Toronto-based, Afghan-Canadian artist whose digital carpets created in Microsoft Excel and Word are always floating between transmediation, taking on the form of being viewed on a digital screen display, to existing in various digital formats, and also existing within the physical modes of print, vinyl, or carpets in collaboration with weavers from Afghanistan. MBTC N1 (2018) showcases only one of the physical forms Zazai’s practice can undertake - and also exists as a carpet outside of the gallery space.

Shaheer Zazai’s artistic practice showcases translations of this form of data between multiple realms and people – crossing cultural, and digital/physical boundaries. His practice can be seen as a representation of the self through culture, and within deeply meaningful cultural items – such as carpets – that hold their own rich cosmologies and forms of storytelling.

All of the artworks in “Digital Amalgamations” present varied perspectives on how digital apparatuses have opened deeper understanding of the self, showcasing the complex nuances of what it means to be human within a digitized time. “Digital Amalgamations” invites viewers to evaluate their own relationships and reliance on digital technologies, as well as question preconceived notions of what digital art, and digital art histories, can look like. This exhibition hopes to re-evaluate what being digital even means, beyond the digital screen. Experiencing and engaging with digital technologies as human beings is what gives digital technologies meaning. Like all art, digital adjacent art cannot be experienced or created in a vacuum – it is backed by networks of human communication, interaction, and sharing of knowledge.

1. Erich Hörl, “The Technological Condition,” Parrhesia, no. 22 (2015): 6.

2. Skawennati, “She Falls For Ages,” accessed April 11, 2025, https://skawennati.com/legacy/SheFallsForAges/index.html. In 2016, Skawennati coined the term “machinimagraph”: a still image that was made from a machinima (a style of animation created inside video game graphic engines).

3. Treva Michelle Pullen, “Skawennati’s Timetraveller™ Deconstructing the Colonial Matrix in Virtual Reality,” AlterNative An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 12 no. 3 (2016): 244, DOI:10.20507/AlterNative.2016.12.3.3.

4. David Gaertner, “Indigenous in Cyberspace: CyberPowWow, God's Lake Narrows, and the Contours of Online Indigenous Territory,” American Indian Culture and Research Journal 39, no. 4 (2015): 59.

5. Brendan Keogh, A Play of Bodies: How We Perceive Videogames (The MIT Press, 2018), 22, https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/10963.001.0001.